Regular research on the traces of ancient metallurgy in the area of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains started in 1955 by the History of the Polish Metallurgical and Iron Casting Technology Team appointed by Kazimierz Bielanin and Mieczysław Radwan within the Science and Technology History Department of the Polish Academy of Science (Bielenin 1992, 6; 2006, 13) together with the Academy of Mining and Metallurgy from Cracow. In 1960 the Museum of Ancient Metallurgy from the Świętokrzyskie Region was opened in Nowa Słupia (Bielenin 1992, 211-213). In the neighbourhood of the museum Mieczysław Radwan started his experimental research already in 1962 alongside the archeological excavations and inventory works. The research aimed at reconstruction of the ancient slag-pit furnace process. (Bielenin 1992, 55-59). In 1967 the research was transformed into a public demonstration event at the suggestion of the members of the Polish Tourism and Country-Lovers Society from the Kielce district.

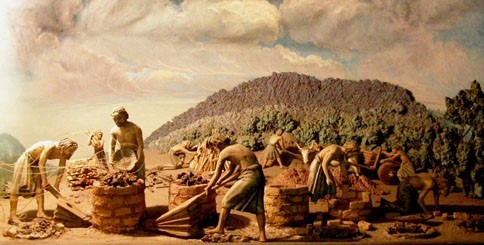

Diorama with the representation of ancient metallurgists’ work in the Museum of Ancient Metallurgy from the Świętokrzyskie Region located in Nowa Słupia. (photo by A. Durazińska)

The initiative was widely accepted and at present it is known as a popular event under the name of ‘Dymarki Świętokrzyskie’ archaeological event. (Bielenin 1992, 214-215) At the beginning the scenography of the show was completely unconnected with the realities of the Roman times as they were known at that stage. The reason was not so much lack of knowledge on the topic but rather ignoring it by the scientists whose main focus was the reconstruction of the direct reduction process. [1]. The group conducting experiments was mostly interested in a slag-pit furnace technological process and making a rapid progress on its reconstruction. Preparing a ‘slag-pit furnace’ show in the form related to primeval reality was of no importance at the time. It resulted in the creation of an unconstrained vision of the metallurgical district in the Świętokrzystkie Mountains in its time of active functioning. (Bielenin 1992, 215). The vision included warriors in strange helmets made on the basis of motorcycle helmets or robes of ‘metallurgists’ resembling the legend of the Piast the Wheelwright. There were also other elements of ‘historical’ parade scenography when iron ore was transported from Rudki to Nowa Słupia on horse carts. The form was not constant and homogeneous, it changed with years. Wooden structure of the so-called ‘furnace cluster’ [2] was a loose interpretation of the ‘ancient city’ which was to protect the area of slag-pit furnace experiments. Some elements of ancient cults were there as well – a type of a ‘Holly Grove’ inspired by Slav mythology and folk legends. Country folklore was an ideal substitute for what could not be created on the basis of the sublime image of the slag-pit furnace metallurgists from the Świętorzyskie area frequently identified as our ancestors. It is worth mentioning that such false identification takes places also today. Apart from the already mentioned reasons underlying the way the slag-pit furnace scenography was demonstrated there was yet another one of major importance, namely interest and engagement of the authorities of Polish People’s Republic as well as politically active party members, which allowed the enterprise to continue even in the times of economic crisis and the period of Martial Law. A visible effect of this period of ‘prosperity’ is the conviction of many people that the event reached its prime in 70s and 80s together with its idyllic image of ancient metallurgy in the Świętokrzystkie Mountains (Banaś, Przychodni 2003, 21-23). It is difficult to debate about or fight this belief and attachment to the created tradition. The objective of the above description is not to discredit this ‘heritage’ and rather to indicate that though it added to a rich and colourful history of the discussed enterprise, it cannot be at present treated as an example to follow, especially in the face of new challenges naturally indicating the need to use the ‘Dymarki’ festival for the region’s promotion. Social and economic conditions have changed completely for such forms of promotion. It was noticed by local authorities over 10 years ago. Administrative reform from 1998 contributed to the change as well as shaped the importance of local authorities which after this date started treating their heritage differently. The ‘myth of splendor’ accompanying the archaeological festival caused that its programme was created with the ambition to remain an event of a mass character. The aspects connected with popularizing scientific research results remaining the core reason for the enterprise creation were fortunately left in the hands of the people interested in the topic of the ancient iron metallurgy in the Świętokrzystkie Mountains.

[1] Apart from the already mentioned research pioneers the following names should also be listed: Adam Mazur, Elżbieta Nosek and Wacław Różański.

The first ‘Dymarki Świętokrzyskie; archaeological festival in 1967. Photo by Central Agency of Photography - Wawrzynkiewicz.